Emily Whitehead was 6 years old and near death at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia when she became the first pediatric patient to receive yet-to-be approved chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy to treat her leukemia. Today, she is 18 and in full remission.

Emily is one of many success stories of CAR T-cell therapy in the treatment of blood cancers. The science behind this game-changing treatment has progressed remarkably since the first two types of the therapy received Food and Drug Administration approval in 2017, with many new forms being studied.

But, as with many cancer therapies, CAR T doesn’t always eradicate the disease and it may still progress in a significant number of patients following treatment. And, if CAR T-cell therapy fails, standardized treatment protocols have yet to be determined to stop the cancer from growing, though some treatments have shown limited success.

CAR T-cell therapy is predominantly used for patients after two or more other therapies have failed. It was initially considered a treatment of last resort. In many cases now it is being used as an earlier form of treatment.

“We are moving CAR T-cell therapy up sooner in treatment. A recently published study showed that when patients have an early first relapse of their diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) patients have better outcomes,” says Leslie Popplewell, MD, Medical Director of Hematology and Blood and Marrow Transplant at City of Hope® Cancer Center Atlanta.

In this article we will explain:

- What is CAR T-cell therapy?

- What is the CAR T-cell therapy success rate?

- What happens if CAR T-cell therapy fails?

- What is the future of CAR T-cell therapy?

If you’ve been diagnosed with a blood cancer, such as leukemia, lymphoma or multiple myeloma, and have questions about your treatment plan, or if you’re interested in a second opinion on your diagnosis, call us or chat online with a member of our team.

What is CAR T-cell therapy?

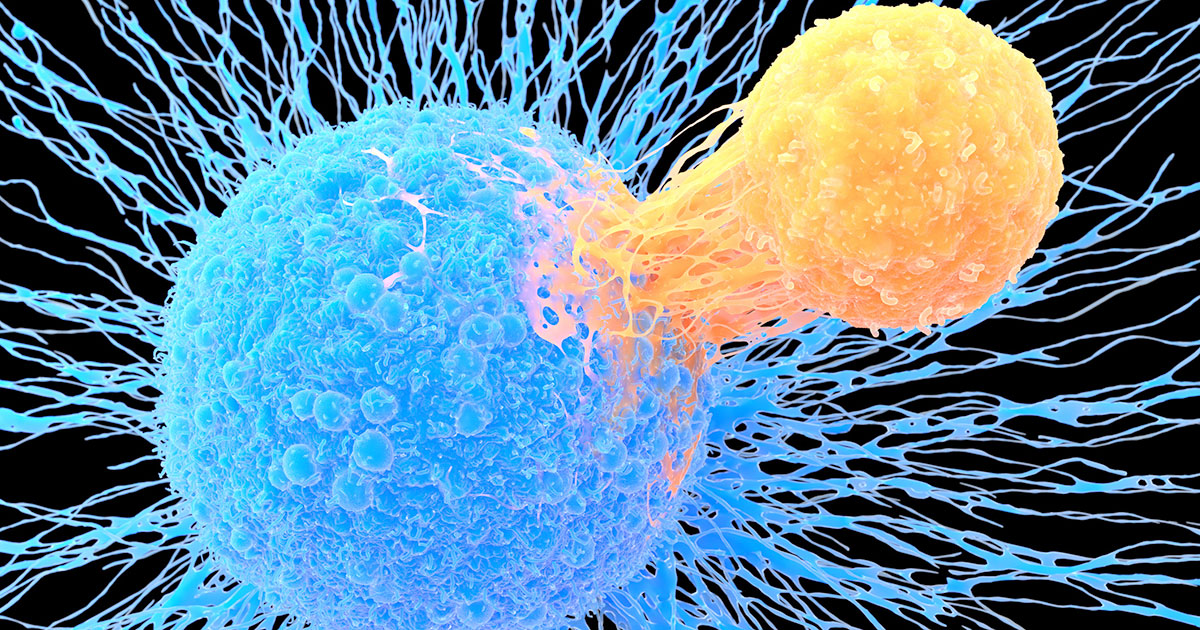

T-cells are white blood cells that the immune system produces to help destroy foreign cells. T-cells have receptors that can latch onto the antigens (proteins) on the surface of cancer cells, but a patient’s T-cells do not have the specific receptor needed to successfully identify and fight his or her cancer.

Laboratories can now alter a patient’s T-cells to produce the needed receptors through the CAR T-cell process.

First, some of the patient’s T-cells are removed through apheresis, a process similar to blood donation. Blood is removed from the patient, it is spun in an apheresis machine to extract the T-cells. The rest of the blood is returned to the patient’s blood stream.

Technicians send the removed T-cells to a laboratory, where they are modified into CAR T-cells that are better equipped to fight the patient’s cancer. The lab re-engineers the T-cells by inserting genetic information that directs the T-cells to make receptors for the specific type of cancer cells in the patient.

The modified cells, now designed to better identify and kill the patient’s cancer cells, then need to be multiplied before being infused into the patient’s body. The patient typically undergoes a lymphocyte-depleting regimen of chemotherapy prior to the infusion of the CAR T-cells.

“CAR T-cell therapy has really begun to displace autologous stem cell transplants as the preferred treatment for diffuse, large B-cell lymphoma [DLBCL] in early first relapse,” Dr. Popplewell says. “The complete remission rate is well over 50 percent.”

CAR T-cell therapy that targets the CD19 antigen is now approved for relapsed and/or refractory B-cell lymphoma and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. B-cell maturation antigen-(BCMA) targeted CAR T-cells are approved for relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma.

What is the CAR T-cell therapy success rate?

A CAR T-cell study out of Massachusetts General Hospital, reported in Blood Advances in July, looked at 100 patients who received some form of CAR T-cell therapy for lymphoma, myeloma or B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. While the purpose of the study was to measure a patient’s quality of life following treatment, its data showed 56 percent of the participants received a complete response and 24 percent had a partial or very good partial response to the treatment.

That left a substantial minority of patients in the study still experiencing disease progression following therapy, and 38 percent of the study group died within a median follow-up period of 14.5 months (ranging from 0.4 months to three years). The median time between diagnosis and the infusion of CAR T-cells for the study’s patients was 39.8 months.

A 2019 study in the New England Journal of Medicine found a 40 percent complete response and a 12 percent partial response in the 93 patients who had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma—a type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma—and who had previously received or been ineligible for an autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation.

A 2023 study published in April in Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology reported on trials that showed complete response rates of 40 percent to 54 percent for relapsed and/or refractory aggressive B-cell lymphomas, 67 percent in patients with mantle cell lymphoma, and 69 percent to 74 percent in patients with indolent B-cell lymphomas.

What happens if CAR T-cell therapy fails?

Studies are underway to consider the best strategies to use when CAR T-cell therapy is unsuccessful.

One treatment doctors may recommend is a second CAR T-cell infusion. Blood, a publication of the American Society of Hematology, published a study in January 2021 that investigated the effectiveness of a second round of CAR T-cell therapy. It found that “second infusions of CD19 CAR T-cells were feasible and led to durable responses” for some patients.

Another possibility, if CAR T-cell therapy fails, is the use of bispecific antibodies, a form of immunotherapy. These antibodies have two receptors on them, typically designed for one receptor to attach to a T-cell and the other to a cancer cell. The bispecific antibody acts like a pair of handcuffs, bringing the two cells together and making it easier for T-cells to detect and attack the cancer cells.

“Bispecific antibodies are not yet FDA-approved in second-line treatment,” Dr. Popplewell says. “So, they are saved for third line or later, and can be effective even after CAR T-cell therapy. We might also consider them for people who might not be eligible for CAR T-cells because of comorbidities or other issues. There are no head-to-head trials comparing CAR T-cells to bispecific antibodies yet.”

A study in Blood in December 2022 of 550 patients with multiple relapsed or refractory DLBCL found the most commonly used systemic treatments after CAR T-cell progression are:

- Chemotherapy with the drug lenalidomide

- Targeted Therapy

- Chemoimmunotherapy

- Bispecific antibodies

- Radiation therapy for localized progression

Of those patients, complete responses were reported for 14.3 percent receiving bispecific antibodies, far better than other treatments.

What is the future of CAR T-cell therapy?

Much more study is being given to CAR T-cell drugs, both to improve their efficacy and reduce the negative side effects of treatment.

“CAR T-cells are one of the biggest advances that I’ve seen so far in my career,” Dr. Popplewell says. “I think that we’re really in an age of incredible discovery for the treatment of cancer in general, but lymphoma and myeloma in particular, and I think the rate of progress continues to increase.”

That progress includes the following.

Newer versions of CAR T-cells

“CAR T-cells are probably not in their final iteration yet,” Dr. Popplewell says. “You can change the kind of cells that you use. Right now, we're using T-cells, but there's a lot of interest in using natural killer cells as the vehicle for cancer treatment. There's a lot of interest in switchable CAR T-cells or bispecific CAR T-cells.”

Improved production of the CAR T-cells

“CAR T-cell manufacturers are now working on a manufacturing platform that will allow more rapid manufacturing time and that’s in clinical trials right now. And it looks very promising,” Dr. Popplewell says.

Use of off-the-shelf CAR T-cells

“The other thing that’s coming along are off-the-shelf CAR T-cells. Right now, none of those are FDA-approved, but it would be nice if we could have the CAR T-cells already manufactured and ready to go,” Dr. Popplewell says.

“Identifying a patient, getting them through all the testing, getting insurance approval, getting a manufacturing slot, collecting the cells, it just takes time,” she says. “And during that time, especially with aggressive lymphomas, you can have progression of disease. So, shortening that time can only be a benefit to the patient.”

Off-the-shelf CAR T-cells would have the original T-cells come from a donor, not the patient. The donor-produced CAR T-cells would be infused in the patient, similar to an allogeneic stem cell/bone marrow transplant, where a matching donor’s cells are used in the transplant instead of the patient’s own stem cells.

“It’s using T-cells from another person, transducing those so that they are CAR T-cells and then freezing them and having them ready,” Dr. Popplewell says. “It would be great if you could just give a patient CAR T-cells without all the wait time.”

For all these reasons, Dr. Popplewell remains optimistic about the future of CAR T-cell therapy.

“CAR T-cell therapy is not in its final form and we’re going to see dramatic improvement in every aspect of CAR T-cell therapy,” Dr. Popplewell says, “from our ability to treat side effects to our ability to make the treatment even more effective than it is already. And, who knows, eventually we might be using CAR T-cells as a frontline therapy for lymphoma.”

If you’ve been diagnosed with a blood cancer, such as leukemia, lymphoma or multiple myeloma, and have questions about your treatment plan, or if you’re interested in a second opinion on your diagnosis, call us or chat online with a member of our team.