We all know how old we are chronologically. But do we know how old we are biologically? Everyone ages at a different pace. Lifestyle, genetics, stress and other factors contribute to keeping us younger than we look or aging us beyond our years. One telltale sign of the inner aging process may be found deep inside each of us, in tiny strands of DNA proteins at the tips of each chromosome. For years, scientists have been studying the role these chromosome tips, called telomeres, play in measuring our biological age and how they influence the development of disease, including cancer. One learning their research has gleaned is that telomeres nurture cellular health and allow cells to thrive. "They're like little fingers at the end of the DNA," says Stephen Lynch, MD, Primary Care and Intake Physician at our hospital near Phoenix. "They protect cells and enable cells to fix errors in the DNA during the process of cell division.” Another important fact scientists have noticed about telomeres, Dr. Lynch says: “They tend to shrink with age."

What are telomeres?

Telomeres have been compared to aglets, the plastic or metal tips at the end of shoelaces that prevent them from fraying. When an aglet is damaged or worn out, the lace begins to unravel. Telomeres shrink with each cell division or replication. As we age, telomeres become too small to protect the chromosome, no longer preventing cell damage from occurring—and that may create a breeding ground for cancer cells. "Cancer is the end result of an evolutionary process called aging," says Maurie Markman, MD, President of Medicine & Science at Cancer Treatment Centers of America®(CTCA). "It's the end result of all the cell divisions, reproductions and mutations that occur over many, many years."

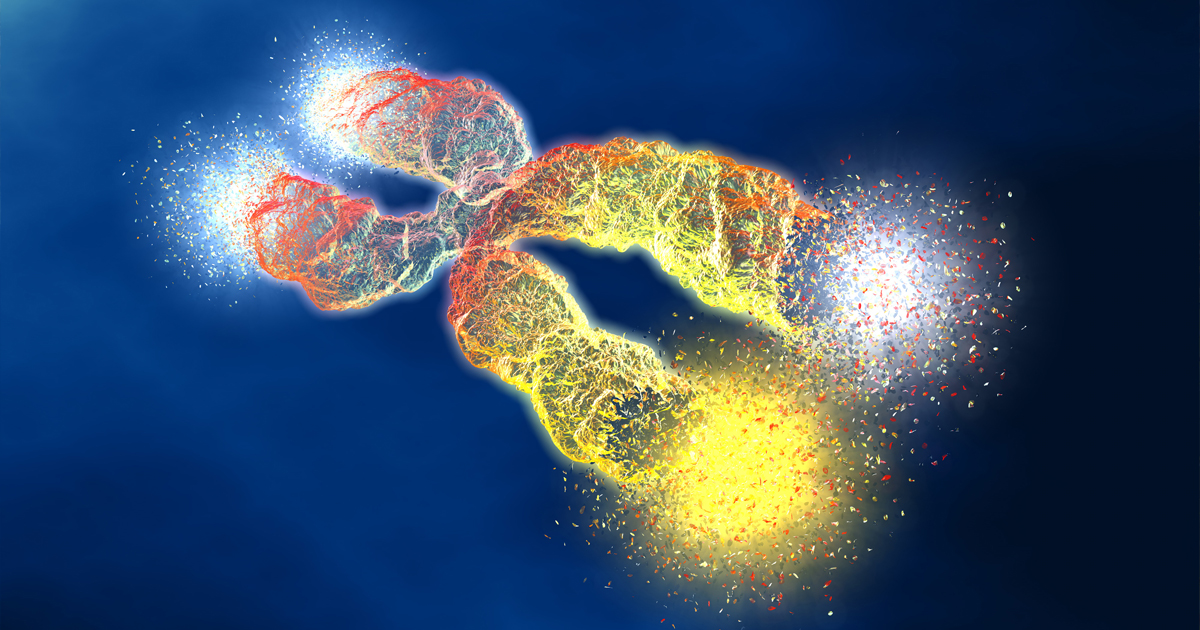

So, if telomeres shrink with age and age is a leading risk factor for cancer, do longer telomeres reduce the risk of getting cancer? Researchers at Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston suspect the answer may be yes, theorizing that telomere length "can affect the pace of aging and onset of age-associated diseases." Meanwhile, scientists at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston have concluded that shortened telomeres appear more frequently in cancer patients. Researchers there studied telomere length in dozens of patients diagnosed with a variety of cancers. Their conclusion: "Short telomeres appear to be associated with increased risks for human bladder, head and neck, lung, and renal cell cancers." These studies suggest that shortened telomeres that are no longer able to protect DNA lead to cell death, cell mutations and/or senescence, a zombie-like state that cells reach when they have stopped functioning.

Telomere facts

- Telomeres are repeating sequences of DNA found at the tips of human chromosomes.

- Telomeres are made up of base pairs, the matching sets of nucleotides that make up the rungs of the ladder in the DNA helix. Telomeres can be 15,000 base pairs long.

- Each time a cell divides, its DNA loses up to 200 base pairs. The number of base pairs lost may depend on stress and other lifestyle influences.

Just as shorter telomeres have been linked to aging, disease and deteriorating health, longer telomeres have been associated with a healthy lifestyle, which may lower cancer risk. "Studies show that people who run a significant number of miles tend to have longer telomeres," Dr. Lynch says. "We know that exercise is good, and it keeps you healthy. Well, maybe one reason is that telomeres may help you maintain the integrity of your DNA." A University of California San Francisco (UCSF) study concludes that changes in lifestyle, including increased exercise and an improved diet, can lengthen telomeres. "These findings indicate that telomeres may lengthen to the degree that people change how they live," author Dean Ornish, MD, UCSF clinical professor of medicine, says in a UCSF article on the study. "Research indicates that longer telomeres are associated with fewer illnesses and longer life."

Predictably, this science has led to theories that telomeres can be manipulated to reverse aging. In a 2010 article published in The Harvard Gazette, scientists said they used telomerase, the enzyme that feeds telomeres, to reverse aging in mice. The mice became significantly healthier when they were given the enzyme, according to the researchers. Organs regenerated, brain cells became more active, and the males regained their fertility. "What really caught us by surprise was the dramatic reversal of the effects we saw in these animals," says Ronald DePinho, then a Harvard researcher and former president of MD Anderson.

In addition to feeding telomeres, telomerase is a powerful enzyme that may be found in many cells, including embryonic cells, active immune cells. But the enzyme is also found in cancer cells, raising concerns that rather than preventing age-related cancer, it may stimulate tumors. Despite research supporting telomeres' role in healthy living, and despite multiple clinical trials exploring their role in cancer and other illnesses, no evidence has been found to suggest that telomere research will lead to immortality or miracle cures. So for now, the Fountain of Youth remains elusive. "We are not designed to last forever," Dr. Lynch says. "Father Time remains undefeated."